Oxford County, Maine

Coromoto Minerals

The 2004 Season at Mt.

Mica

---- March-April

-----

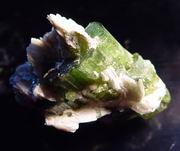

A 10 cm tourmaline from pocket 3 coated with cleavelandite and lepidolite

Coromoto Minerals

The 2004 Season at Mt.

Mica

---- March-April

-----

A 10 cm tourmaline from pocket 3 coated with cleavelandite and lepidolite

The winter of 2003-04 passed painfully slowly for me as I awaited the arrival of Spring. By late the previous year Richard and I had mined right up to the Plumbago pit. Removing the muck inside of their pit late last year showed us how rich the pegmatite was. Intense lithium mineralization was readily visible wherever one looked and we were only looking at what Plumbago had left in the floor. Large masses of lepidolite, spodumene crystals to 1 meter and thick layers of triphylite were abundant. The Dagenais pocket of '79, the largest pocket found at Mt. Mica, was still visible in the pit floor. As we were cleaning the muck from the pocket, our excavator broke a piece of ledge exposing a large multi-colored tourmaline in matrix. We were astounded. This was new for us even though we had been mining at Mt. Mica diligently for 6 months. It is obvious to me now why miners from Hamlin to Plumbago had not mined the western end of the pegmatite where we had just spent the last 6 months. The only Li mineral that we encountered there was monterbrasite. They simply followed the lepidolite and stopped working in the western direction when it gave out. Nightly during January and February visions of lepidolite and tourmaline, like those from a Wendell Wilson picture, unsettled my sleep. Happily, Plumbago had left a little pegmatite for us to look at before it was necessary to tackle once again the ever thickening over burden above the pegmatite. In the southwestern corner of the  pit they

had removed much of the schist above a 50x60 foot section but had

not mined the pegmatite. Our test holes showed there was only

4-8 additional feet of schist to be removed. Unfortunately, the

pegmatite had plunged about 6' up dip of the section. This plunge, added

to the 30 degree dip of the pegmatite, meant that if we were to mine this

section, we would first have to drop our road down 6-8 feet. The plunge

was probably what prompted Plumbago to abandon this portion . The road work was to be 'dry' excavation, since

although we were mining pegmatite, Plumbago had removed the part above

the garnet line. Below the garnet line there is nothing of interest at

Mt. Mica. This exercise consumed 2 weeks of steady work in

cold weather. By mid April though we were ready to do some real

mining. While cleaning the ledge to start

benching, we noticed a broken drill steel protruding into the rock.

Richard speculated that Plumbago had gotten the steel stuck in a

pocket. This was a pleasant thought and soon we would know the answer.

During March, Richard had already taken some of the schist from above

this section so we had a few feet we could work immediately. As we got looking more

closely at the cleaned ledge it was plain to see that Plumbago had drilled and

blasted numerous holes in this area without breaking the rock.

There was no free face into which the blasted material could move. They obviously

suspected there was something there worth mining. For us, it would be

easy work for we now had a 6 foot deep free face in front of this area. pit they

had removed much of the schist above a 50x60 foot section but had

not mined the pegmatite. Our test holes showed there was only

4-8 additional feet of schist to be removed. Unfortunately, the

pegmatite had plunged about 6' up dip of the section. This plunge, added

to the 30 degree dip of the pegmatite, meant that if we were to mine this

section, we would first have to drop our road down 6-8 feet. The plunge

was probably what prompted Plumbago to abandon this portion . The road work was to be 'dry' excavation, since

although we were mining pegmatite, Plumbago had removed the part above

the garnet line. Below the garnet line there is nothing of interest at

Mt. Mica. This exercise consumed 2 weeks of steady work in

cold weather. By mid April though we were ready to do some real

mining. While cleaning the ledge to start

benching, we noticed a broken drill steel protruding into the rock.

Richard speculated that Plumbago had gotten the steel stuck in a

pocket. This was a pleasant thought and soon we would know the answer.

During March, Richard had already taken some of the schist from above

this section so we had a few feet we could work immediately. As we got looking more

closely at the cleaned ledge it was plain to see that Plumbago had drilled and

blasted numerous holes in this area without breaking the rock.

There was no free face into which the blasted material could move. They obviously

suspected there was something there worth mining. For us, it would be

easy work for we now had a 6 foot deep free face in front of this area. All last winter, and as we prepared our road this Spring, the thought gnawed at me that Mt. Mica may be 'drying up' down dip. In his 1895 book on Mt. Mica, A.C. Hamlin theorized that the peg would become unproductive down dip as the 'light of heaven' was required to form gems. ( 'The History of Mount Mica',1895, page 50). He did not confine the necessity for sunlight to only tourmaline, however. Most gems stones, he theorized, needed the 'contact of the air or a ray of sunlight'. I am not a proponent of the sunlight theory, but I did notice that last year we found fewer pockets down dip and none below the plunge mentioned in the last paragraph. It appears to run the entire length of the peg. Maybe Plumbago had the same experience prompting them to leave the section below this plunge. Local lore has it that Plumbago considered the plunge to be 'the kiss of death'. After weeks of work enabling us to access this unmined section, would we learn a hard lesson? To my great relief, our first cut into this new section exposed some lepidolite. This was the first lepidolite we had exposed at Mt. Mica through or own efforts. Now we were getting some where and it was satisfying. Our second cut, just in front of the stuck steel, opened a pocket. To our amazement this pocket contained quartz crystals with the white rod inclusions and blue apatites very similar to the ones we found last year. I, for one, was convinced we would never find another of these odd apatites feeling they were a phase confined the margins of the pegmatite. What was going on? Our next slice along our down dip bench opened another pocket behind the first. This one contained just a few quartz crystals. However, working at the thickening cleavelandite with chisels produced some lepidolite rimmed mica books and lots of bright blue triphylite. Mary, my wife, was in China attending to our company's affairs. I called her in Beijing and strongly encouraged her to join us for the next week of mining. Mary's timing all last year had been bad as most of the productive pockets we opened just before she arrived and or just after she left. Now her timing would prove to be right on the money. While we waited for Mary, we took another  slice

from the schist overburden, a two day project. Once this was

completed our next bench across the pegmatite

exposed little except a robust cleavelandite layer. Worry was setting

deeper roots and we were considering telling Mary to leave

town. While drilling

the next series, we encountered some mica on the eastern end of our working face.

Thinking that this might portend a pocket, we decided to shoot only the

middle 3 holes hoping that we might break into the pocket. Shooting all

of the holes might cast the pocket out onto the muck pile. After the

blast, I walked to the edge of the pit to observe the ejected

rock. Richard asked me,' Is the floor green with tourmaline'. 'I don't

know',

I cautiously replied. What I did see was lots of rusty rock. This is

always a good sign because it means fluids had stained the rocks

indicating a pocket may be close by. slice

from the schist overburden, a two day project. Once this was

completed our next bench across the pegmatite

exposed little except a robust cleavelandite layer. Worry was setting

deeper roots and we were considering telling Mary to leave

town. While drilling

the next series, we encountered some mica on the eastern end of our working face.

Thinking that this might portend a pocket, we decided to shoot only the

middle 3 holes hoping that we might break into the pocket. Shooting all

of the holes might cast the pocket out onto the muck pile. After the

blast, I walked to the edge of the pit to observe the ejected

rock. Richard asked me,' Is the floor green with tourmaline'. 'I don't

know',

I cautiously replied. What I did see was lots of rusty rock. This is

always a good sign because it means fluids had stained the rocks

indicating a pocket may be close by.  The

face just before the

blast

went off was very white, so something was going on. I heard the

sound of

water pouring into or out of something as well. When we got

into the pit we could see our rusty rock was riddled with small

grass green tourmalines. What a transition had occurred!

The

face went from showing little to be being studded with hundreds of

small tourmalines. These started almost at the upper contact in albite

lined vugs and ended

in the cleavelandite just above the garnet line. Closer examination

showed the larger tourmalines consisted of green overgrowth on schorl.

The

terminations of the crystals, though , were green and as much as 1 cm

thick. On the right side of

this new exposure there was a tourmaline that showed a green

termination hanging from a small pocket. This was a large crystal and

we were to

spend the next 2 hours trying fruitlessly to extract it in matrix.

Despite this falure, we were

encouraged that large tourmaline was forming in the pockets. Left is a

small 3 cm group that came out near the large one above. In the

picture below Mary and Richard pose beside the new exposure. The

face just before the

blast

went off was very white, so something was going on. I heard the

sound of

water pouring into or out of something as well. When we got

into the pit we could see our rusty rock was riddled with small

grass green tourmalines. What a transition had occurred!

The

face went from showing little to be being studded with hundreds of

small tourmalines. These started almost at the upper contact in albite

lined vugs and ended

in the cleavelandite just above the garnet line. Closer examination

showed the larger tourmalines consisted of green overgrowth on schorl.

The

terminations of the crystals, though , were green and as much as 1 cm

thick. On the right side of

this new exposure there was a tourmaline that showed a green

termination hanging from a small pocket. This was a large crystal and

we were to

spend the next 2 hours trying fruitlessly to extract it in matrix.

Despite this falure, we were

encouraged that large tourmaline was forming in the pockets. Left is a

small 3 cm group that came out near the large one above. In the

picture below Mary and Richard pose beside the new exposure.The following day we  returned to continue to explore the area and check

all of the small vugs in the surrounding feldspar. As the productivity

of this effort waned, we decided to risk it and shoot a single hole

just to

the right of the productive zone and slightly behind it. This 8' deep

hole

opened up more of the rusty area revealing more cleavelandite and

small

vugs. Again we attempted this maneuver moving the single hole yet

closer to the hot zone. After this next blast, we came down into the

pit

to see a bushel basket sized mass of mud hanging from the

ledge face. We had

blown the face off of a sizable pocket and a good deal of its floor as

well. By this time we had gouged a sizable hole in the pit floor

directly below this precariously suspended mass. The hole quickly

became the pit sump hole as it rapidly filled with water. Not a good

thing.

We immediately placed a 5 gallon bucket beneath the material in hopes

of catching it before it fell in the our new sump. This was a wise

move, for

the moment we probed the pocket mud , a large amount of it fell

into the bucket with a

resounding thud. Several more buckets were filled in this matter

without us examining closely any of the material as it was dropped in.

Even so,

we could see a the occasional lustrous green termination in the pocket

debris. What we had or had not found would have to wait until we washed

and screened the material. Once emptied, this pocket, like the one

from yesterday, consisted of a mud filled interior and rusty base of

lepidolite and an outer shell of at least 15 cm of cleavelandite.

The cleavelandite was quite friable and could be dug with one's bares

fingers. Above the main chamber several smaller chambers radiated

back into the ledge and each of these contained more tourmalines. returned to continue to explore the area and check

all of the small vugs in the surrounding feldspar. As the productivity

of this effort waned, we decided to risk it and shoot a single hole

just to

the right of the productive zone and slightly behind it. This 8' deep

hole

opened up more of the rusty area revealing more cleavelandite and

small

vugs. Again we attempted this maneuver moving the single hole yet

closer to the hot zone. After this next blast, we came down into the

pit

to see a bushel basket sized mass of mud hanging from the

ledge face. We had

blown the face off of a sizable pocket and a good deal of its floor as

well. By this time we had gouged a sizable hole in the pit floor

directly below this precariously suspended mass. The hole quickly

became the pit sump hole as it rapidly filled with water. Not a good

thing.

We immediately placed a 5 gallon bucket beneath the material in hopes

of catching it before it fell in the our new sump. This was a wise

move, for

the moment we probed the pocket mud , a large amount of it fell

into the bucket with a

resounding thud. Several more buckets were filled in this matter

without us examining closely any of the material as it was dropped in.

Even so,

we could see a the occasional lustrous green termination in the pocket

debris. What we had or had not found would have to wait until we washed

and screened the material. Once emptied, this pocket, like the one

from yesterday, consisted of a mud filled interior and rusty base of

lepidolite and an outer shell of at least 15 cm of cleavelandite.

The cleavelandite was quite friable and could be dug with one's bares

fingers. Above the main chamber several smaller chambers radiated

back into the ledge and each of these contained more tourmalines. Back at home after careful screening , sorting , ultra-sonic cleaning and the rust removal in a crock pot of oxalic acid, the extent of what we had found was begining to emerge. The first striking piece was the one pictured at the top of the page. Mt. Mica was not noted for showy specimens but this one was a 'keeper'. In the material there were many terminations of high luster and grass green color. Most crystals appeared to be like the original ones in that they were green overgrowth over schorl. Some, though, were decidely green throughout. There was little material of cutting quality. As a Maine miner guility of a manifestly provincial attitude, Vandall Kings's comment in the introduction of volume 1 of the 'Mineralology of Maine', a must own work, continues to challenge me. In it he suggests that Maine's pegmatites are not on a par with those of San Diego county in Southern California. Although probably true, it is our ambition to place this assesment in the questionable category. For me at least, a beautiful and unique specimen is more valuable than finest gem rough. At this point we are the farthest down dip that any miners have tackled Mt. Mica. Perhaps the mineralization of the pegmatite may rapidly decline. On the other hand we could be on the cusp on a new and more thrilling phase of this wonderful pegmatite's story.....................gmf/4/04

|

|||